Simulating debris collection in space

The researchers at the lab of the Competence Center for Intelligent Sensors and Networks use AI models to train a camera for its deployment in space. Its mission? Clean up dangerous space debris.

For many decades, sustainability only played a minor role in space travel. That is why today, many thousands of disused satellites and debris from explosions and collisions are floating in earth’s orbit. But failing to remove the larger pieces of space debris puts future space missions in serious peril.

Circularity in space

Environmental protection and circularity are no longer just terrestrial concerns. Sustainable development reached outer space some time ago, and removing space debris from high-traffic orbits continues to play a key role. See also:

Tüfteln für die Müllabfuhr im Weltall

ESA Space Environment Report 2025

How to build a circular economy in space

In the framework of the ESA’s Clean Space Initiative, the CC ISN works with Sirin Orbital Systems AG to develop an intelligent space camera. The idea behind it:

- The camera captures image data of the targeted object with an image sensor.

- With the help of AI models, this data is then used to determine the object’s position and location relative to the hunter satellite.

- The hunter satellite’s control unit uses this information to approach the target object safely and autonomously.

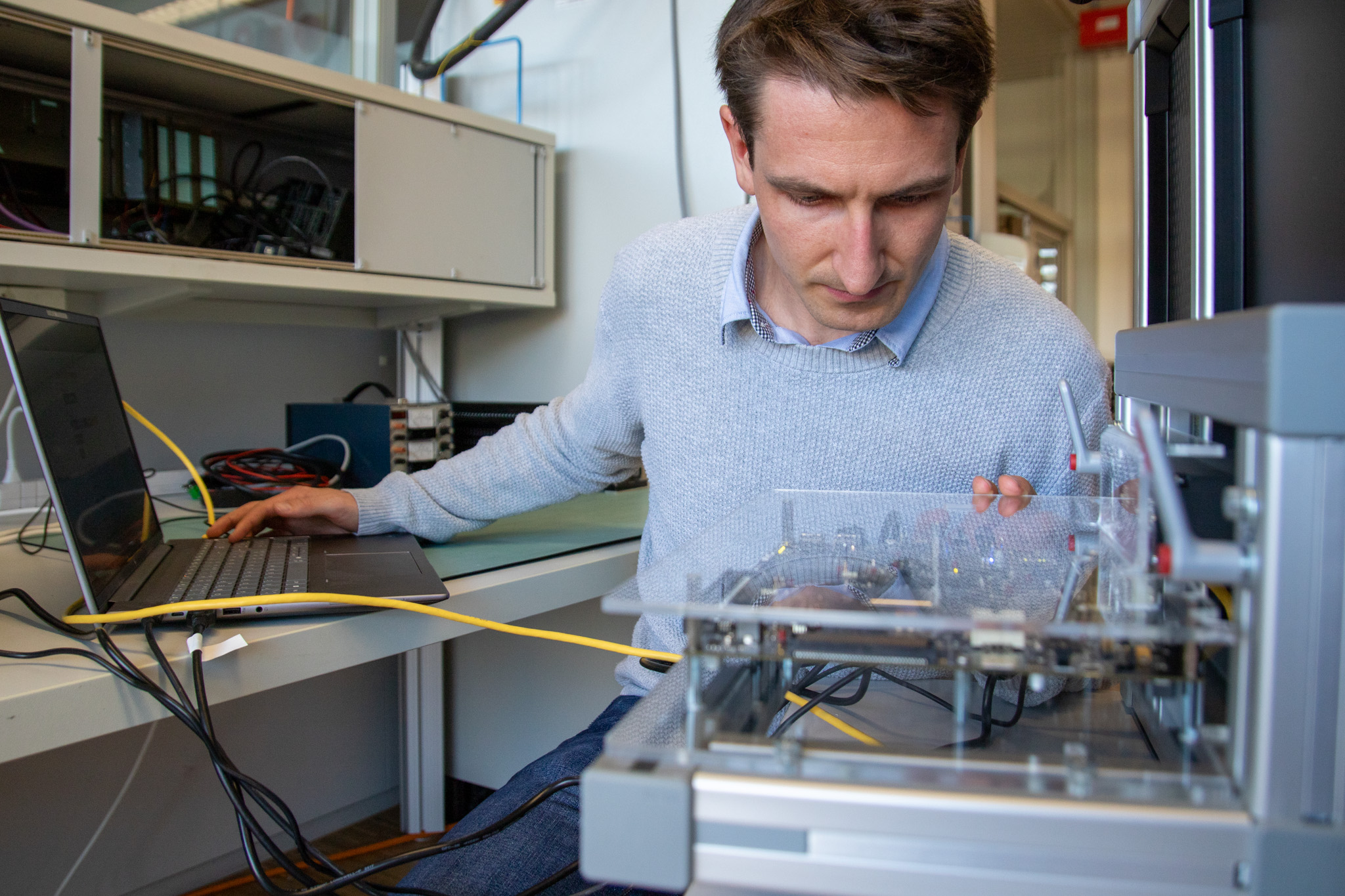

Testing space technology in the HSLU lab

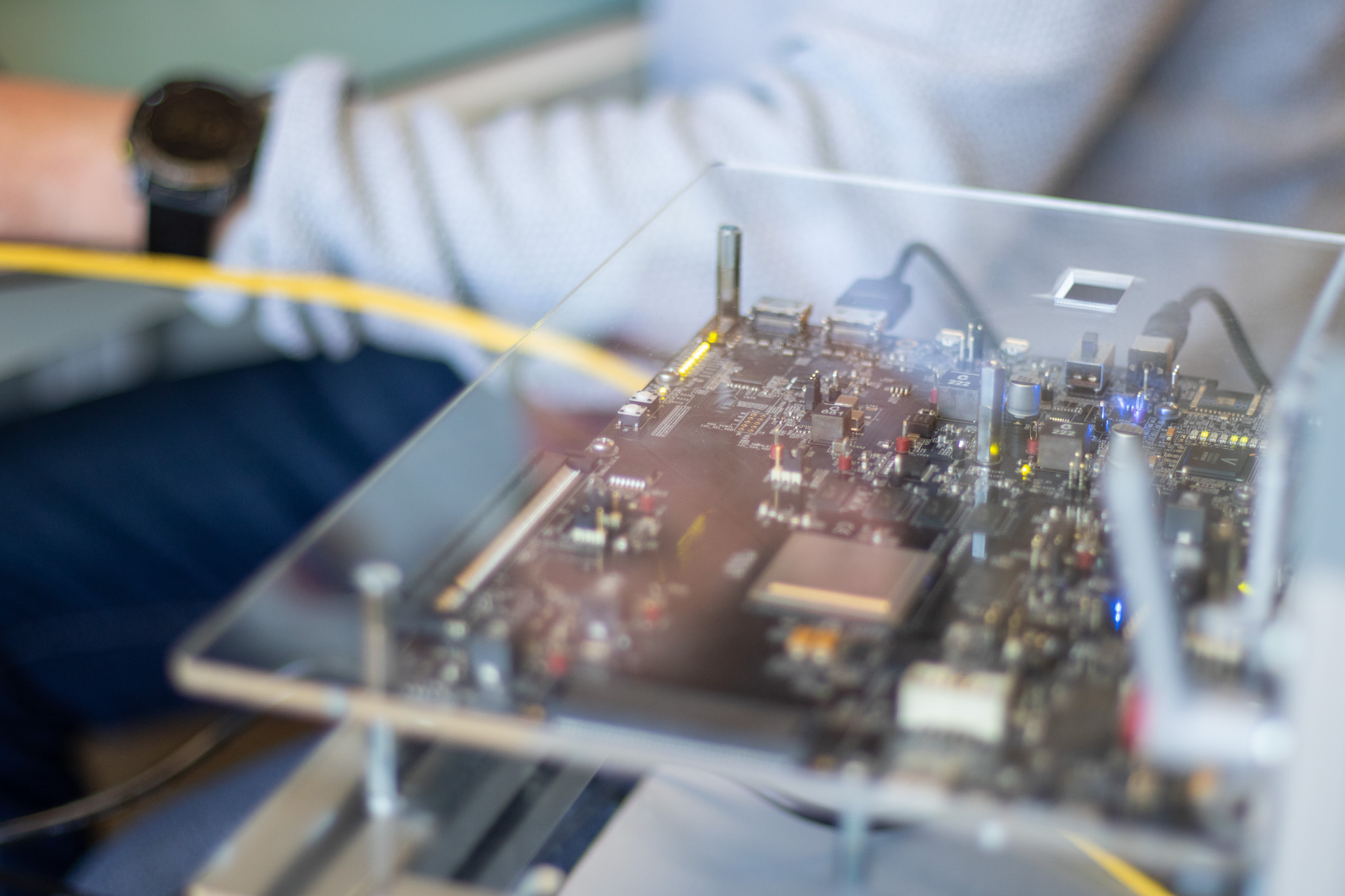

One of the researchers’ recent successes is an initial prototype of the camera on a hardware platform that’s ready for use in space: a so-called FPGA (Field Programmable Gate Array) System-on-Chip (SoC) specifically designed for the harsh operating conditions in space. Head of Research Group Jürgen Wassner and his team could draw on their extensive expertise in developing FPGA solutions for complex signal processing tasks such as the Powerline Train Backbone technology for the digital freight train.

The first question to address was how to test the camera before it is launched into space. There aren’t nearly enough real-life images from space to train the camera’s AI models. And how could the team realistically simulate the movements of the target objects and the hunter satellite in their orbit around Earth in the lab?

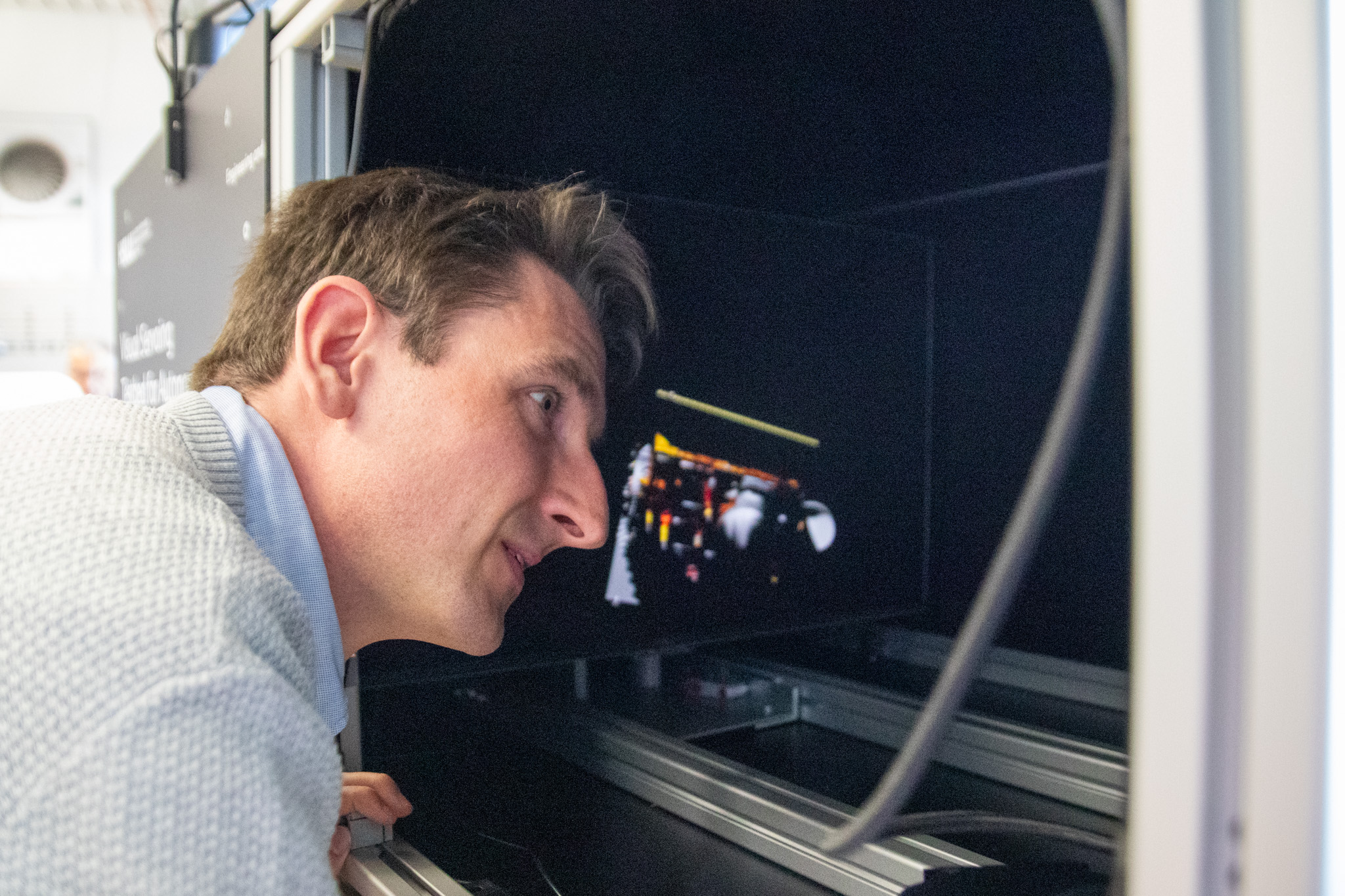

How the Visual Servoing Testbed works

The researchers went on to build a testbed tailored to addressing these challenges in a SERI-funded project.

- The testbed works with digitally generated visuals—actual moving objects are not required.

- Artificially generated images closely simulate the situation in space,

- and astro-dynamic modeling ensures that the objects in the generated images move exactly like their real counterparts in space.

With this test environment, any volume of high-quality training data for the camera’s AI models can be generated. But there’s more: in a different operating mode, the camera itself can be tested in realistic conditions. To this end, the trained AI models are executed in a so-called camera-in-the-loop simulation on the FPGA SoC platform. The tests show how the entire camera system—including the image sensor—performs in real-time operation.

Visual or mechanical, or both?

The ESA’s GRALS (Guidance Navigation and Control Rendezvous, Approach and Landing Simulator) test lab follows a different approach. There, the research focus is on robot-controlled satellite models (known as mockups) that simulate movement in space. Both in shape and appearance, the mockups should be as similar as possible to the real objects in space.

It’s unclear which approach will eventually prove fruitful. Quite possibly, both methods will be necessary to reliably test technologies for image-based navigation in space under lab conditions. The Foundation for the Promotion of the Lucerne School of Engineering and Architecture supports the activities of the researchers at the CC ISN. This funding allows them to contribute to the international discourse on the topic in a meaningful way.

The human eye as a model for an energy-efficient camera

Testing the camera is just one of the challenges the researchers are facing: the very limited energy budget aboard the hunter satellite is another. That is why the camera’s AI models must learn to control their energy hunger.

Here, the team of the CC ISN takes inspiration from the human visual system. In the human eye, signals from approximately 100 million photoreceptors are compressed onto approximately 1 million nerve fibers in the optic nerve and transported to the brain as electrochemical impulses. The brain then builds an image of the environment from these impulses.

Thanks to the Adrian-Weiss Foundation’s generous donation to the HSLU Foundation, the team is now ready to test a novel image sensor modeled after human eyesight. Combining it with spiking neural networks, which are a type of artificial neural network, the researchers hope to further reduce the energy consumption of the space camera.

The space camera is ready for the next level

The plan is to have a visual test environment and a prototype of the space camera by the time the current project wraps up. But the team’s work won’t be finished—far from it. The researchers will progress to the next stage, aiming to refine the camera to a higher TRL (Technology Readiness Level) through a requirements-based development process.

Technology Readiness Level (TRL)

Originally conceived at NASA in 1974, the TRL system is now a nine-level scale estimating the maturity (technology readiness) of a technology. Its use is no longer confined to the space industry but common in many other areas with higher safety standards such as avionics or railway and medical engineering. A simple, but compelling way to describe the nine TRL levels involves unicorns: https://www.granttremblay.com/blog/trls

One thing is for sure: the researchers will continue to blend artificial intelligence with their own to help advance sustainable development in space.

Comments

0 Comments

Thank you for your comment, we will analyse it.