Business Transformation Management,

If nothing has been frozen, nothing must be unfrozen again

Author: Andreas Jäger Fontana

Digitalisation, globalisation, and demographic change not only enable new forms of work and organisation. They become an imperative. Organisations must reinvent themselves permanently. What does this mean for the development of teams in organisations that are caught between hierarchy and self-organised agility?

Organisational transformation

Rigid structures and formal hierarchies in traditional organisations seem to run counter to the imperative of organisational transformation. Formal hierarchy in organisations is comparable to the protocol in diplomacy, the programme in computer science or the routines in group dynamics. Formal hierarchy serves the efficient reproducibility of the predictable. But formal hierarchy is not designed to deal with the unexpected. For this reason, many organisations are creating room for collaboration in self-organised, fast-forming, constantly rearranging and dissolving networks.

Of Gangs and Squads

The team as a form of organisation is not a new phenomenon. What has changed over time, however, is the economic and social environment in which organisations and their teams operate. The founder of Scientific Management, Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856–1915), demonised by many today and often torn out of his contemporary context in attempts to pay tribute to him, did speak of gangs. Today, in times of agile organisation and collaboration, many talk about squads. The term «gang» does not necessarily refer to a group of criminals. As with Frederick Winslow Taylor, a «gang» is a hierarchically structured organizational entity. In contrast, a “squad” does not belong to the hierarchy of an organisation. It rather tries to have a self-organized impact off the beaten track.

What are the characteristics of teams in organisations?

Teams have a common task that their members pursue together. No team does what it does for itself, but for others (clients, stakeholders). In my opinion, teams and their members should therefore think consistently in terms of product, service, mandate and mission, customer. The individual members of a team contribute to the team’s success in different ways (roles and contributions). They are faced with specific expectations of how they should contribute to the team’s success (norms and rules). Even if it is not always clear and visible who belongs to the team and who does not, a team always distinguishes itself as part of an organisation from its environment (belonging). Demarcation potentially goes hand in hand with the much-invoked sense of «we» (identity). To cope with a common task, to clarify roles to be assumed, to formulate mutual expectations, to shape the relationship to one’s own environment, teams need time (stability).

Teams and hierarchy

As early as the 1990s, Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas K. Smith named their Team Basics for successful teamwork, i.e., at the same time as Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber developed Scrum as an agile framework for product development. According to Katzenbach and Smith, it is common sense that teams cannot be successful without a clear purpose. Only a motivating challenge and a shared sense of accountability turn a group of people into a team, not any team-building exercises or workshops.

It is also worth considering what Katzenbach and Smith, summarised in the term Uncommon Sense, say about the ideal relationship between hierarchy and teams. Hierarchy and teams go together. Hierarchy does not need to be threatened by teams. Those who see teams as a substitute for hierarchy would miss the true potential of teams. On the one hand, hierarchies are essential for the functioning of organisations. On the other hand, teams would turn performance into learning. Learning takes place primarily in teams, where it emerges from the reflection of experiences made. Organisations benefit from «The Wisdom of Teams» (as their book is titled) in many ways. This applies both to traditional, hierarchical organisations and to new forms of work and organisation, for example in squads.

How to recognise the functioning of teams?

Scientific research into group dynamics goes back significantly to Kurt Lewin (1890-1947) and his epoch-making contribution in the journal Human Relations in 1947. Lewin sees groups as self-regulating systems that are in a state of permanent change. To grasp the dynamics in groups, he proceeds analytically in three steps: (1) description of the initial state, (2) description of the forces acting on each other in the group and (3) description of the resulting new state.

The members of a group influence each other through their behaviour. Individual expectations and perceptions are shaped by group norms and standards. If such norms and standards prove to be counterproductive, it is important to break them and replace them with new ones. The analytical three steps become a proposal for proceeding in three steps in practice: «Unfreezing, Moving, and Freezing of Group Standards». With his methodological approach, Lewin wanted to help managers to discover what is happening in their teams and thereby enable them to diagnose the functioning of teams. Lewin’s themes – stability of groups and permanence of their norms and standards – take on a whole new relevance in today’s era of ongoing organisational transformation. Where nothing has been frozen, nothing must be unfrozen again. Teams are in «moving» mode all the time.

Alternative to team development as an intervention

With regards to the conscious, planned and targeted development of a team, the question immediately arises as to by whom a team is developed, for what reason and with what intention, and on whose initiative? Does a team itself have the desire to develop or does the impetus come from outside, from the team leader or from the organisation of which the team is a part? Does the team leader see himself/herself as part of the team? How does he/she interpret the role of managing the interface between the team and its environment? Will external consultants be brought in?

Teams are constantly changing and developing, according to Kurt Lewin, at every moment of their existence. Teams react to changes in their environment, to changing tasks, to changes in their composition and leadership. It is therefore surprising that team development is usually understood as an intervention. How are such interventions usually planned, prepared, implemented and evaluated? Like projects. Projects, by definition, always have a beginning and an end. But thinking in terms of «beginning» and «end» no longer does fit the dynamics of ongoing organisational transformation.

So how could a team be developed differently? Do not design team development as an intervention. Shift the focus of your «team development» instead to where it takes place anyway: into the daily work of the team. External interventions are not able to do this.

Focus team development consistently on the factors of successful teamwork

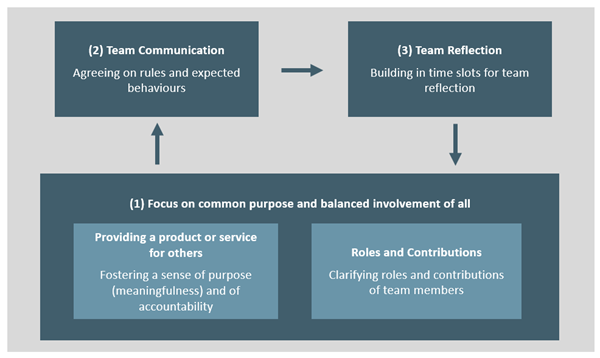

Team development should consistently focus on those characteristics of teams in organisations which, at the same time, are factors of successful teamwork: (1) permanent focus on the common purpose with balanced involvement of all team members, (2) communication in the team encouraging team members to speak up and (3) recurring reflection in the team.

Aligning the team consistently to its purpose and clients, brief moments of team reflection at regular intervals using peer consulting promise success. These are not new insights, but they become increasingly important in a world of VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity).

![http://Herausgeberband%20Leadership%20und%20People%20Management]](https://hub.hslu.ch/leadership/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2022/07/Herausgeberband-Leadership-und-People-Management-1-e1658915072433.jpg)

Kommentare

0 Kommentare

Danke für Ihren Kommentar, wir prüfen dies gerne.